- Home

- Michael Callahan

The Night She Won Miss America Page 2

The Night She Won Miss America Read online

Page 2

Betty can no longer detect even a faint whiff of the lemon cake. “You want me to enter a beauty pageant?”

Her mother places her dishrag on the table, begins wiping a stain that’s been there at least two years. “It’s about more than beauty, Betty,” she says. The table surface squeaks under the rag. Wipe, wipe, wipe. “The girls who are already entered are some of the most achieved young ladies in the state. Athletes, scholars, performers. It’s a great honor to be asked.”

Betty wants to point out that her mother has already made this questionable assertion, but lets it go. She wonders if girls who enter pageants are even allowed to eat cake. She doubts it. Mulling over this is better than considering the dilemma before her now. Agreeing to enter a ridiculous bathing beauty pageant will surely get her mother into the Junior League. That’s the can-do spirit we’re looking for! Declining will surely kill her chances. She pictures her mother, sentenced to a lifetime of exclusion, sitting silently at games of bridge and dinners at the Wilmington Country Club and listening to the women chirp on about all of their good works and the committees and Oh, that speaker last month was just divine!, and Yes, he was. And so good-looking! Titter-titter. She has no interest in a pageant whatsoever but ponders whether she has it in her to deny her mother. She remembers their trip to see the Miss America Pageant seven or eight years ago: all of the lights, the pretty girls, the electric moment when the winner was announced. Miss California, Rosemary LaPlanche! Funny how she can recall the name so clearly. If she had any flicker of desire to be on the stage herself, it has been long extinguished. The mere thought of appearing in a swimsuit in front of an auditorium leaves her paralyzed.

She needs to buy time, find an excuse that her mother cannot refute.

“You need a talent to enter something like that,” she offers.

“Darling, you play beautifully!” comes the rapid reply. Her mother has anticipated every objection. Betty can see this is going to be more difficult than she anticipated. She has gone into battle impulsively, against a foe bearing far heavier artillery. The fact is that Betty plays adequately. The harp, a lavish gift from her grandmother. Exceedingly challenging to learn, but Betty was both precocious and determined as a child. How many years of lessons? Six? Seven? Her performance at the high school talent show was a raging success, but in truth it was her trio partners, a violinist and a cellist, who did Vivaldi’s heavy lifting. Betty is hardly ready for the Kay Kyser Orchestra. But to argue such logic is pointless. They’ll get her another tutor. Fly in Harpo Marx if they have to. She pictures herself in a flowing evening gown, harp tilted to her chin, thrumming “A Tree in the Meadow” in front of an auditorium in some musty hotel in Wilmington. A chill zips down her back.

“Mother, I know this is important to you, but I just—”

“Of course, dear. I understand. It’s a lot to ask. If you would really rather not, I’ll simply call Mrs. Howell and tell her you decline. Simple as pie.”

Or cake.

Betty sighs audibly. The humble understanding, the faux posture of I support whatever you decide, underneath which lies I will be bitterly disappointed if you do not do this for me—I ask so little of you. Betty closes her eyes, wills the entire conversation away, knowing she has already been defeated.

“I’ll think about it.”

“Delightful,” her mother says, almost in a squeal, and for a moment Betty is gratified that she has done this, made her mother so happy. Because I’ll think about it always means yes. How many people say, “I’ll think about it,” and then decide in the negative?

But . . . oh. A beauty pageant. Betty stares down at the hulking slab of lemon cake her mother has sliced for her—on the nice china, how subtle!—and, picking up her fork, wonders if she can gain twenty pounds before the contest. Disqualified for girth! But as she chews the moist, delicious cake, she knows this is folly. She will enter Miss Delaware; she will play her harp; she will come home with a nice ribbon for entering. Her mother will join the Junior League. All will be well. It’s one day, for goodness’ sake.

After all, Betty thinks, it isn’t like I can actually win.

༶

“I still cannot believe you are doing this.”

Patsy is lying on her stomach on Betty’s bed, which Betty now realizes is too pink, too juvenile for a young woman of nineteen. It’s almost as if her mother is trying to keep her a girl, frozen at eleven years old. A sense of foreboding she has been fighting for weeks descends again, threatens to compromise the feigned look of disinterest she now wears like a mask. She is scared to death. None of it makes any sense, so she has stopped trying to make sense of it. Instead she simply flits through the days, like a butterfly fluttering through the garden. It’s easier.

“I can’t believe how much I have to pack,” Betty says. “You’d think I was going away for a year. And speaking of which, I thought you were coming over to help.”

“You’ve been shopping for weeks. Didn’t your evening gown require, I don’t know, ten fittings?”

“Which one?”

“The important one.”

“Six.”

“Six. Six! My sister didn’t need that many for her wedding gown, and she got married at the Hotel du Pont, I remind you. I just can’t believe you are doing this.”

“It would be helpful if you would stop saying that. I would think by now your disbelief would be over. I believe it should be very clear that I am indeed doing this.” She has to.

She has won Miss Delaware.

She closes her eyes. Deep breath, she commands internally, feeling the air fill her lungs, slowly seep out of her nostrils.

This is the hidden cost of being the good daughter, the good student, the good girl. People take advantage: with flattery, with emotional manipulation, one slice of lemon cake at a time. Sometimes she feels like more of a receptacle than a real living person. Someone other people project their aspirations, goals, ideas, and tasks onto. And she simply accepts them, like a bank teller taking deposits, perfunctorily fulfilling one request after another: Watch your brother. Practice your harp. Set the table. Stay away from him. Get smart. Go and change—that’s not appropriate. Watch your tone. Do your homework. Get the mail. Do it all over again.

But then, it is her own fault, is it not? You cannot play the good girl, relish the rave reviews and metaphorical standing ovations from the critics—your parents, your teachers, your neighbors, your boss at the dress shop—and then complain that everyone only sees you as dutiful and earnest, with no thoughts or real depth of your own. And so she endures: the dull lectures at the college her parents chose; the wallpaper in her bedroom her grandmother chose; the expectations, or lack thereof, that society has chosen, not only for her but for every girl like her. And who would feel sorry for her, decree she has been cheated or slighted? She has had advantages most other girls would kill for.

And yet.

She cannot tamp down the disquiet, the small knot of adrenaline that continually sloshes around her stomach like a peach pit. She has dismissed it as nerves, attributed exclusively to the fact that she must now subject herself to an entire week of something far worse than a sociology lecture or overly floral decor. But in her most solitary moments—in this moment, folding clothes as Patsy idly flips through the pages of Glamour and spouts girlish nonsense lying on the bed—Betty knows better. She knows. And the knowing is the worst of it.

She realized, with all due horror, that she was going to win Miss Delaware as soon as she walked into the hotel in Wilmington. Betty had expected a girl from every county and charitable organization, and had instead found just seven others like herself, a solid half of whom failed to disguise the feeling that they’d had no idea how they’d gotten roped into this.

Clearly there had been more than one lemon cake baked.

One by one, like dominoes, they fell. One girl’s voice cracked like a shattering ice cube as she attempted Verdi; another’s evening gown looked like it been made before the war, perhaps f

or a maiden aunt, and then been hemmed and tucked and sewed into something passable. During the question-and-answer portion, another girl couldn’t explain what Truman’s Fair Deal was but did somehow manage to relay the story of Grady the cow, a 1,200-pound Hereford that had made national headlines a few months earlier when it got wedged in a silo door in Oklahoma. It was hardly surprising when Betty’s harp solo—Salzedo’s “Chanson dans la Nuit”—and answer to the question “Do you feel there is a divide between today’s youth and adults in American life?”—she’d answered that throughout history there have always been divides between generations, but rather than cause alarm, we should be encouraged, because this is how new ideas are formed and progress is made—left her with the crown. Her mother—and, to her surprise, her father and brothers—had overflowed with pride. It had all been something of an unexpected lark. Until Betty realized what was coming next.

Atlantic City.

“Stop, stop, stop!” Patsy is saying, stretching out from the bed and grabbing her forearm as Betty shoehorns a nightgown and slippers into her case. “You’re packing like you’re going off to prison. Come over here for a minute. Stop being a crazy beauty queen. Good golly! It’s me, remember? Talk to me.”

Betty plops beside her on the bed. “It’s all pretty silly, isn’t it?” she says. “Look at this.” She reaches over, retrieves the Miss America Pageant yearbook she has been sent. Bios and pictures of fifty-two young women, some from cities—Miss Chicago, Miss New York City—most from states, all vying for the storied title of Miss America 1950.

Patsy is still on her elbows, flipping through. “Wow. Some of these girls are really pretty.”

“You sound surprised. Are you worried people will think I simply wandered in?”

Patsy rolls her eyes. “Horse feathers. You’re a dish and you know it . . . Holy cow! Miss Michigan is a dead ringer for Lizabeth Scott.”

“I just never stopped to think that this whole thing could get this far.”

“Eh, you did it for your mom. That’s not a bad reason.”

“It’s not a particularly good one, either.” Betty gets up, resumes packing. She stops in front of the dresser mirror. She has been doing this incessantly as September has crept closer. It’s bad enough she is missing a week of classes for this, but what really bothers her is the constant self-examination, the picking apart of her cheekbones and hair and lips and eyes and brows. Weighing herself against the competition, when she has sworn to herself, more times than she can count, that she doesn’t care about any of this. Except that it’s evident that in fact she does, which is the most annoying thing of all.

“This is a great picture of you,” Patsy remarks from the bed. Patsy begins reading aloud. “ ‘Betty Jane Welch was born on May 12, 1930, in Dover, Delaware, and is the first titleholder in five years from the nation’s first state, winning over a formidable field. About to enter her sophomore year at Maryland State Teachers College at Towson, she is an A student and will be exhibiting her talent as a harpist. She is 5'6" and weighs 118 pounds, with strawberry blond hair and hazel eyes. Her interests include tennis, swimming, and crafts.’ ” Patsy crinkles her nose. “Crafts?”

“I had to put something. It was as good as any. After all, I can be crafty.” Meant as humor, comes off as pathos. Patsy is the one person who can always see behind any façade she puts up.

Patsy scoots off the bed to stand next to her, her arms reaching over, hands interlocking to pull Betty closer. Betty recalls a day long ago, both of them barely tall enough to see over this dresser, when they had looked into this same mirror, weighed down in her mother’s jewelry, their tiny mouths sloppily smudged with lipstick. Dress-up never ends.

“You act like you’re going off to the guillotine,” Patsy says, tilting her head onto Betty’s shoulder, addressing their joint reflection. “You are Miss Delaware! You get to spend a week in Atlantic City, getting your picture taken and feeling like a princess. You’ll be on the radio, for God’s sake! And you could win some terrific scholarship money. And I’ll be there Saturday with your family to root you on. And don’t forget the best part.”

Betty smiles in spite of herself. Patsy can always manage to make her smile, even in the sorriest of circumstances. “Well, don’t keep me in suspense,” Betty says back to their reflection. “What’s the best part?”

“The escorts,” Patsy says, winking. “Every contestant gets one of the local college boys as an escort for the week. Your future husband could be standing in front of his own mirror right now, wondering what it will be like to meet you.”

“Wonderful,” Betty replies, reaching up to place a hand atop Patsy’s arm. “Some awful rum pot who’s probably six inches shorter than me and perspires profusely, and will spend the week stepping on my toes during every dance.”

“C’mon, Bett,” Patsy says, in a soft, gentle voice she does not use all that often. Her mouth turns up into a crooked smile. “Look at this as a wonderful caper. What’s the worst that could happen?”

Two

Atlantic City is marvelous. Certainly not elegant or refined or couth. But it is most certainly, unequivocally, crazily marvelous.

It has never been a weeklong destination for the Welches. For them, every summer brings the rental of a lovely beach cottage in Rehoboth, save for four years ago, when they packed up to visit her grandparents in Morristown, New Jersey. A four-hour drive, Simon and Ricky fighting the entire way.

Atlantic City, she thinks, must be a fun place to be a child. But after only a night here, Betty can see it is far more fun to be an adult. She is, of course, deeply enamored with the flashing lights and marquees of Steel Pier and Steeplechase Pier and Heinz Pier, their myriad distractions and amusements and shows and thrill rides. Last night she simply strolled the length of the Boardwalk, inhaling the smell of sea air mixed with fresh popcorn, sawdust, fudge, and eau de toilette splashed on by giggling girls trying to attract the attention of swaggering boys.

But it is the nightclub marquees and restaurant signs and beckoning awnings that have left her enraptured. Marty Magee’s Guardsmen in the Mayfair Lounge at the Claridge; the Irving Fields Trio at the Senator; the sign above Tony Baratta’s Escort Bar at the corner of Atlantic and Missouri, tantalizingly asking, “Wouldn’t You Rather Have the Best?” She fantasizes not about being Miss America, but of sitting at a table at the 500 Club or dancing all night at the Hialeah. She forlornly reminds herself that a week’s worth of pageanteering will surely preclude any of it.

Like all of the hotels that line the Boardwalk, the Traymore—located in the heart of town on the Boardwalk at Illinois Avenue—is enormous, a dusk-colored sand castle capped by two tiled golden domes in its center that glint in the late morning sun, and which looms like a mythic Xanadu above the beach. The bathtubs here are legendary; each has four faucets, one each for hot and cold water, one each for hot and cold ocean water.

Betty cannot understand why anyone would want to bathe in ocean water.

Breathe. Breathe.

It is Labor Day, and there is a bustling hum in the art deco lobby that contrasts with the stately accoutrement of the space—its huge semicircular windows that face the ocean, the dramatic sheer drapes, green velvet chaises, and tasteful Oriental rugs. A sign at the far end advertises Lenny Herman appearing in the Submarine Room, “the mightiest little band in the land, with Nancy Niland.” Chagrined visitors check out, mark the official end of their summers, going back to their lives and the approaching coolness of autumn. An ebullient din emanates from those arriving, a tossed-together sorority of girls here to register for the pageant in the Rose Room by six p.m., the official deadline. Betty conjures an image of a harried girl scurrying in at 5:57, frantically trying to scribble her name in before her sash is discarded into the nearest bin for tardiness. She laughs out loud at the thought.

“Please, share the joke! I could use a laugh right about now.”

Betty glances up just as a girl sits down next to her on the sofa, artful

ly crossing her legs. She must be a pageant contestant as well, but at first glance she seems incongruous as a Miss Anything. She is dark and beautiful in a femme fatale type of way, the kind of mysterious siren who lurks in the shadows in gangster movies, secretly in love with the informant. Her chestnut hair is done up in a top reverse roll, the center peak arching up into an almost perfect question mark, the sides big fluffy rings that frame her angular face. She wears a plain gray dress with short melon sleeves and black single-sole pumps, and clutches a small polished silver case in her right hand. She extracts a cigarette, proffers the case to Betty, who demurs. “You sure?” the girl says. “Last chance before we enter the convent. From here on out, it’s the rules of Mother Abbess over there.”

Betty follows the girl’s sightline, spies a matronly woman in enormous pearls with curly, prematurely graying hair in the corner, holding court with four other contestants. “That’s Lenora Slaughter,” the girl says. “She’s the boss lady. Runs the whole show. Trust me, you don’t want to get on her bad side. She can make sure every judge hates you before you even put on your first pair of stockings.”

Betty looks back to her new companion, now taking an artful drag on her cigarette. “You’re a contestant?” She says it with unintended incredulity.

The girl laughs. “Hard to believe, I know. But yes, you are looking at Miss Rhode Island, in the flesh. Don’t worry. You’re not the only one who’s shocked. Practically everyone’s wondering how I slipped into this thing.” She takes another puff of her cigarette, looks at Betty appraisingly. “Now don’t tell me: You’re too wiry and athletic to be from a New England state, but no tan, so not from warm weather. You also don’t have that annoying midwestern accent. My God, they all sound like pirates. So I’m going to guess . . . Mid-Atlantic. Am I close?”

Betty laughs. “Yes.”

“Ah! See? This should be my talent. I could just come out with a crystal ball and a head scarf. I’d certainly probably score higher than I will belting out show tunes. Let’s see . . . Maryland?”

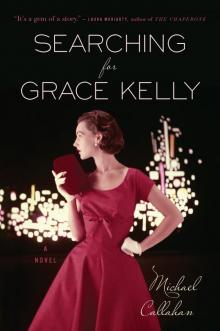

Searching for Grace Kelly

Searching for Grace Kelly The Night She Won Miss America

The Night She Won Miss America